The Blooming Framework: An Interprofessional Framework of Practice for Neurodiversity, Inclusion and Equity in Education.

Neurodiversity is more than a concept or a debate. The variations in human cognition is a biological fact; it is a given that we all think and experience the world differently. This difference can be more apparent in children as they haven't yet learned the protocols, and sometimes 'constraints', of social conventions (and often can't see why they should). These conventions have been socially constructed and maintained for generations, creating a prescribed set of actions, responses and beliefs expected from the members of a given community.

But what happens when an individual does not follow the prescribed norm? What happens when he/she doesn't respond to the expectations imposed by that norm? They become at risk of feeling/being excluded, simply because of how they are ‘perceived’(as identified by the “Social Model of Disability”[1]). Therefore, as educators (but also simply as humans), it is our responsibility to support the inclusion of “all” students, not just “some” students. Isn't that what cultures have been trying to exemplify for centuries through multiculturalism, and what nature has successfully accomplished for millenniums through biodiversity? Different does not equal less, different is more…

This said, knowing and thinking about neurodiversity is one thing, but how do we bridge theory and practice? How do we go beyond intentions and turn those words into actions? How can we best respond to the 4th priority from the Learning Support Action Plan (2019-2025)[2] which highlights the need for more “Flexible supports for neurodiverse children and young people”?

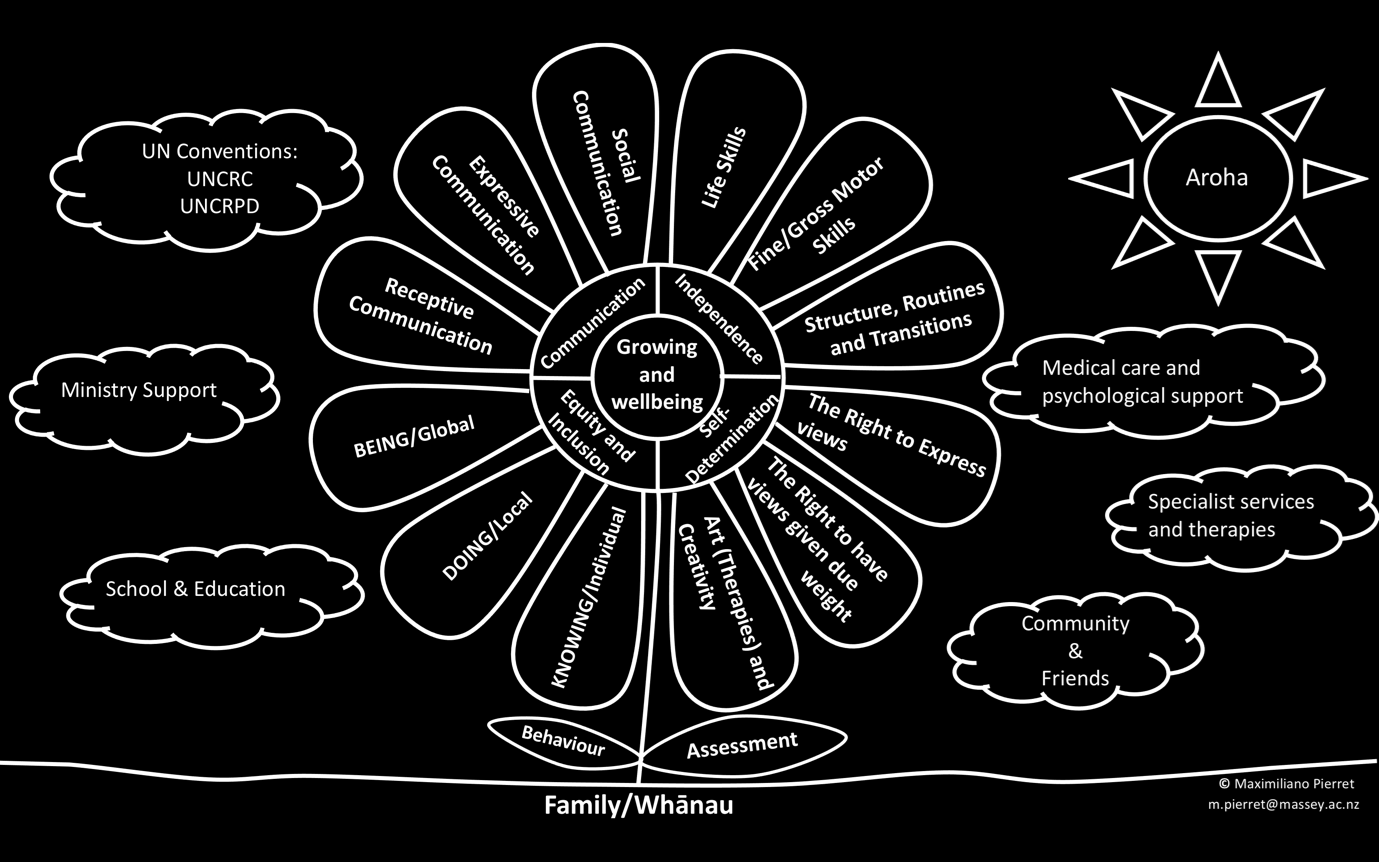

In thinking deeply about these issues, I conceptualised the Blooming Framework, as a holistic and multidimensional framework of practice that recognises the whole child/young person meaningfully in the context of daily life and learning. It is modelled on a strength-based approach, to help children and young people with diverse learning needs to access the curriculum in a multitude of ways and reach their full potential, while also focusing on their physical, social and emotional wellbeing. The aim of the framework is to provide a common compass that can be used by an entire team around the child or young person (including family/whānau) in order to enable every child's educational journey to be as rewarding and nurturing as possible.

The Blooming Framework

At the centre of the framework is the fundamental aspiration of growing and well-being of every student, as these two notions are equally important and deeply interconnected. In order to support this ongoing goal, the framework is divided into four essential areas: communication, independence, self-determination, and equity/inclusion. The three first areas includes child-focus interventions and practices (communication, life skills, motor skills, structure, transitions, etc.), while the fourth area looks at what attitudes, frameworks, pedagogical shifts and practices are needed to best support every child and young person.

The blooming framework can be used as an assessment tool to identify areas of need and support for all students. For example, what is the student’s needs in regard to communication? Can they receive/process the information correctly? Can they communicate and socialise with others properly? Can they achieve everyday tasks independently? Is there an understandable structure in place to indicate to the student what is going to happen during the day (or during an activity) and after? Is the voice of the student genuinely valued and listened to? How? When? How often? Where? By who?

The four areas above require our constant attention as they are essentially linked to children and young people’s learning, growth and wellbeing. One way to use the framework to alert us and the educational team about key areas of attention is to colour each petal of the flower accordingly to the level of need required or support given. It can be done either by colouring the petal gradually from the centre of the flower towards its extremities depending on the quantity of support needed or given; or by colour coding each petal with a different colour that relates to a level of need/support (e.g. Green: Learning needs are being met; Red: Priority areas that need additional support; Orange: Areas to monitor for possible support).

Inclusion and Equity

The fourth area of the framework relates to what does it mean to achieve inclusion and equity through “knowing, doing and being”?

“Knowing” is first and foremost knowing the children/young persons and their whānau, always keeping in mind that each individual is unique and that behind any kind of ‘label’ there is first a human-being. Knowing is to be aware of the child’s challenges but most importantly knowing her/his strengths, abilities, culture and preferences so that they can become the building blocks of teaching and learning. Knowing is also about how the child/young person learns best; knowing their cognitive adaptability and flexibility, sensory sensitivity, physical and physiological challenges.

“Doing” is about making sure that we use Evidence-Based Practice[1], keeping in mind that it is not all about the “research-based” evidence. Research is only one of the three lenses of Evidence Based Practice, the two others refer to the “Practitioner-based Evidence” (the knowledge and skills of the practitioner who is going to implement the intervention or practice) and the “Participant-based Evidence” (the involvement and point of view from the individual her/himself and/or her/his family/whānau as well as being culturally responsive). The other important point around the “doing” is to ensure that we always work interprofessionally, as it is evident that results will be greater if everyone involved in the child’s team works together towards a common set of goals, using everyone’s knowledge, expertise, experience, and strengths.

And last but not least, the “Being”. Being able to project ourselves into the kind of practitioner that we want to be(come). Making sure that we are critical thinkers and self-reflective practitioner at all times. This requires confronting our biases and beliefs, be a willing listener, effective communicator and collaborator. Being empathetic is another important skill to be aware of, as it is the capacity to see things from someone else’s perspective. How would it feel if I was in their shoes or if I was that student’s parent? And a very important aspect of the “being” is to project ourself outside of our practitioner’s sphere to become an advocate, sharing our experience of what has worked (or not), but also sharing positive stories about these children and young people. And sometimes it is simply about the language we use. Why not start to use some of the beautiful words from te ao Māori. For example, doesn’t “Takiwātanga” (in his/her own time and space) sound better than “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, and isn’t “Whaikaha” (to have strength or to be differently abled) more mana enhancing than “Disability”?

It is a no brainer that anyone is more likely to feel a sense of belonging in society if they feel included in that society, and genuinely valued for who they are and what they can do. Enabling the appreciation of neurodiversity in our society should be a collective responsibility and what other best place can one think of than our learning settings? It is time we turn good intentions into actions, we start celebrating differences instead of just accepting them, and keep promoting, enacting and embedding values of inclusion and equity for all.

As this whakatauki from the Te Whariki Curriculum[1] illustrates beautifully: “Whāngaia, ka tipu, ka puāwai“ - “Nurture it and it will grow, then blossom.”

[1] Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement. London: Macmillan Education.

[2] Ministry of Education. (2019). Learning support action plan 2019 - 2025.https://conversation.education.govt.nz/assets/DLSAP/Learning-Support-Action-Plan-2019-to-2025-English-V2.pdf

[1] Bourke, R., Holden, B. & Curzon, J. (2005). Using evidence to challenge practice: A discussion paper. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education

[1] Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood education curriculum. Wellington. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/Te-Whariki-EarlyChildhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf

Maximiliano is originally from Belgium with a mixed cultural heritage of an Argentinian mother and a Tunisian father, and has been living in New Zealand for nearly a decade. He has a Bachelors’ degree in Social Studies, a Masters’ degree in Cultural Anthropology, a Teaching Diploma and a Postgraduate Diploma in Specialist Teaching, specialising in the Autism Spectrum. Professionally, his background has been in education, with almost 15 years of teaching experience both in mainstream (primary and secondary schools) and special education settings. He is currently a lecturer in Neurodiversity, Autism and Inclusive Education in the Specialist Teaching Programme at Massey University, as well as in Postgraduate/Master studies in Inclusive Education.